Latest Comment

Post Comment

Read Comments

Shards of daylight stream through the sparse flora of Anantapuram,the largest of 23 districts in Andhra Pradesh,well past supper time. But the villagers of Raptadu,an unremarkable hamlet that skirts the districts principal town of Anantapur,prepare for darkness earlier. Far earlier.

By about late afternoon,beedi shop vendors and tea stall owners down their shutters,turning away the thirsty. At about the same time,perfumed lovers slink away behind the deserted government school yard,clasping hands and giggling. Their fidgeting never fails to draw a smile from the heavily tanned Nuria Sanchez Garcia.

Perched atop her blue bicycle,Nuria,a 25-year old from Salamanca,Spain,pedals down hard on the red mud path. She was once a professional tennis player,at one point even ranked 450th in the world. At 21,though,she vowed to never touch a tennis racquet again. But today,like every other day of her stay in India,she is about to break that promise.

Ela vunnaru, Nuria says in Telugu,greeting familiar faces on the road with a wave from her bike. Soon though,she will be received in a familiar language. Como estas, the local kids will ask in Spanish,flocking around her as she begins her routine stretches. But now is not that time. There is still some way to pedal before she reaches the clay courts. Time enough to think of her past life,one left behind like the trail of her cycle on the dusty road.

She thinks of how she always wanted to be a tennis star,picking up her first racquet at the age of four. She thinks of how she enrolled at the academy in Barcelona when she was seven,and how she met her batch-mates turned best friends,Carla Suarez Navarro and Nicolas Almagro,now ranked 14th and 15th in the world.

She thinks of how she often travelled around the junior circuits in Spain with that quiet and good-natured boy from Mallorca called Rafael Nadal. She thinks of those living-out-of-a-suitcase days and the struggles of being a low-ranked globe-trotter. A globe-trotter who couldnt ever point out India on a map. India? Ninguna parte middle of nowhere.

Then she thinks of how she shelved her tennis ambitions and started studying human rights law. And how she wanted to do some volunteering work for the underprivileged around the world. And how Nadal got to hear of her plans five months ago. Then he opened his atlas and pointed nowhere out to Nuria.

***

Rafa want me to come,no? So I come here, Nuria says. Just other day,after winning US Open,he email and ask me how I am doing in Anantapur. So I reply and say,I want to be nowhere,always.

Literally in the middle of this nowhere is the first,biggest and dearest project of the Rafa Nadal Foundacion the RDT-Rafa Nadal Educational & Sports School. In his wish to provide an opportunity for children and adolescents with disabilities and from underprivileged surroundings (in the words of the foundations motto),Nadal has pumped in millions of dollars to build five state-of-the-art and flood-lit clay courts,encased within the low platform of a school corridor,in Anantapur. Then three years ago,he personally arrived to inaugurate it.

The foundation aims to use sport as a tool for personal and social reintegration,and Nadals efforts have ensured that hundreds of children from the neighbouring villages have been arriving twice a day,daily,for the past three years to play a sport they hadnt heard of,to study a language (English) that only abroad folk speak and to learn to use a computer,a tool that has brought the universe to Anantapur.

So why Anantapur,you ask? Actually,no one in Spain ever does. The answer lies in a name Vicente Ferrer.

Incarcerated at the now infamous Argelès-sur-Mer concentration camp for his role as an army officer during the Spanish Civil War,Barcelona born Ferrer spent his time pouring over the Bible in 1939. When released a year later,he studied law for four years,dumped it and aimed to become a Jesuit a process that takes 11 years. A missionary by 1951,Ferrer decided to spread the word of god in India. But on arrival in Manmad,Maharashtra,he disowned the Church and decided to help the poor at a physical,rather than spiritual,level.

The result? Sixty-three years later,when Ferrer died at the age of 89 in Anantapur,his funeral was attended by 2 lakh followers,and mourned by at least 2 million the number of lives he immediately improved in the drought-stricken land (the Anantapur region is the second driest part of India,after the Jaisalmer desert in Rajasthan).

The most recognisable face of humanitarianism in Spain,Ferrer was awarded their top peace prize the Prince of Asturias Concord in 1998. A year after he died in 2009,he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize as well.

***

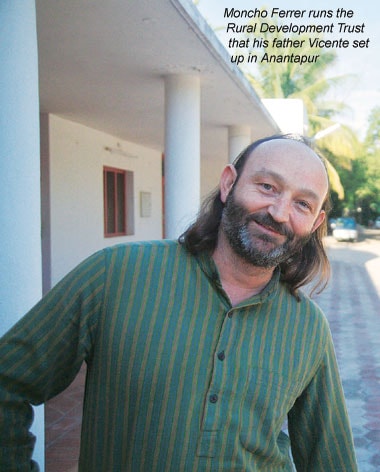

But why the anonymity in India,save a few pockets? Because we have always hated publicity. And my father despised it more than most, says Moncho Ferrer,who heads the Rural Development Trust (now known as the Ferrer Foundation) that his father Vicente founded in Anantapur,back in 1970. Publicity nearly killed him in the first place.

He explains. Back in Manmad,well before he ever stepped foot in Anantapur,my father started this system called the linked brotherhood. It was a simple idea he helped one man dig a well. Then the two of them helped a third. Then the three of them found a fourth. Soon there were close to a 100,000. By 1968,Moncho reckons (often in his first language,Telugu),Manmad,once desolate,was a flourishing land. This is when Life magazine sent down its reporters from the US to do a story on this Marathi-speaking Spaniard. After that,all hell broke loose, says Moncho.

The piece did not go down well with credit-hungry politicians. Moncho says these netas and landowners joined hands to throw Ferrer out of the country. This was opposed by 30,000 people,who walked 240 km in protest.

The then prime minister,Indira Gandhi,had to step in to defuse the tension. She asked my father to return to Spain and come back within a month. Only,it couldnt be in Maharashtra.

So Ferrer chose Anantapur,a move that was apreciated by the Andhra Pradesh government with welcoming arms. But they warned him against the district he had chosen, says Moncho. Nothing is possible in a place that is dirt poor and receives 11 days of rainfall annually, they told him. And my father replied,Great. Thats exactly where I want to be. He spent the rest of his life there,from 1969 onwards.

In the following 40 years,estimates Moncho,Vicente built 1,800 rural schools,six general hospitals and several womens rights centres,family-planning and AIDS clinics. He also encouraged digging of wells and formulation of irrigation schemes. All this was made possible by donations,now amounting to about $15 million a year from Spaniards alone.

***

One of those is Manuel Vazquez,a 33-year-old bank employee from La Coruna,who has been sponsoring the education of two children,Varralaxmi,8,and Chandrakala,10,for two years. It costs about $100 per child per month. So Ive spent roughly $5,000 on these kids so far, says Vazquez thorugh a translator. He is in Anantapur to visit the children for the first time. There was no need for a translator then. When I saw them for the first time in their village,I started crying. And when I left,they started crying.

He has another interesting story to tell about his visit. I had asked some of my friends what to take for the kids. Something I could give to the entire village. They all said,in unison,Sunglasses! So I carried eight boxes,about 300 glasses,to distribute. There was no space to pack clothes because of the sunglasses,so I carried just one T-shirt,one pair of shorts and two underwears. That was fine by me,for its not like I was going to make girlfriends here,no? he says,leaving his translator in splits.

So I gave everyone I saw in the village one each. And soon the next village heard and they came. So I gave them sunglasses too. Soon I was out and one old lady wanted the spectacles I was wearing. I told her,If I give this to you,I will never be able to see my way back. She understood I think.

But what drew him to Anantapur? I had my mind set on Cameroon first. But I faced stiff resistance from my colleagues. They said you either give your money to Anantapur or dont give at all. Another friend wanted to sponsor three kids in Bihar. Again,despite it being in India,he was looked down upon. Again,Anantapur or nothing.

In Ferrer and Anantapur,the Spaniards trust. Nadal,hence,really didnt have a choice.

***

It was early on a Sunday morning October 17,2010 when Moncho Ferrer stood red-eyed under his umbrella. It was one of the 14 times it rained that year,supposes Moncho. Behind him waited a party of people big enough to fill out an army bunker. Some of them were his school friends from Kodaikanal,others were the whos who of the RDT foundation,including the Sports & Cultural Director,Eeli Francis Xavier.

At about 3 am it was when Rafa arrived, says Xavier,who is now on a first-name basis with the 13-time Grand Slam winner. Xavier has personally watched a mud-track for kids interested in running grow into the Anantapur Sports Village,which holds three cricket stadiums (one of them even hosts Ranji Trophy matches),a gymnasium,two hockey fields and as many football grounds. And of course,lest we forget,the latest attraction. The school and tennis complexes that Nadal helped build,and which he helps run by providing $2 million every year. This was inauguration day.

At about 5 in the evening the next day,he cut the ribbon to open his academy. His baby, says Moncho,swelling with pride. I mean,listen,this is Rafael Nadal,standing in a plot of land in Andhra. I had to pinch myself when he pinched the cheeks of a few wards.

Did he eventually play with them? There he was,hitting for close to two hours,trying to lose every point he could,making everyone around him go mad, says Moncho,boasting of the local talent. Hey,I took a point off him too. But he approached the net for a volley. Nadal and volleys,never the best of friends.

One of those kids who Nadal played with during his only visit to the sports academy was Sri Harihara. Having just turned 14,he is one of the darlings at the academy. Today,like many days since his top-spin heavy game (but of course!) blossomed,he has the best court to himself,playing against the best coach in the academy,L Bhaskaracharya. This boy is going places. Already he is playing competitive tennis, says Bhaskaracharya,or Bacchi in short.

Out there,on a surface fine enough to give Monte Carlo or Hamburg a run for its money,Sri Harihara,with trousers folded to his shins like pirate pants and his longish,unkempt hair,is a real sight. His forehand follow-through finishes behind his neck. The impersonation is complete when Harihara pumps his fist,flexes his arms and goes: Vamos! Or belittles himself after a terrible shot with a Culo tondo. Idiota!. Meaning stupid ass and fool respectively.

The kids,all 124 of them in the complex today,adore him. Only some of these children are in the remaining four courts at the time. The others are in either the adjacent computer science lab or in the classroom that teaches English.

***

Repeat after me,there are five classes of nouns,proper noun,collective noun,abstract…, trails off Mahu Basha,the English teacher. In singsong,the children repeat Proper noun,collective noun,abstract…. Basha is thrilled. In this sentence Ashoka is a great king,what is the proper noun? he asks. Supriya Lakshmi,a 9-year old girl from Puttaparthi,shoots up with the correct answer. Basha throws her a tennis ball,sponsored by Nadals gear Babolat. Sundip Reddy gets one too,for telling Surya Krishna,the computer teacher,just what input and output devices are in a computer. Input keyboard,mouse,scanner. Output monitor,printer….

Okay boys and girls,time to go for tennis session now. The tennis ones will go to English classes. And those in English classroom will come here, says Krishna,a digital whiz. From 5 pm-8 pm,in batches of three,they rotate. But most of them want to be part of the 7-8 pm tennis session. For its held under lights. And its taught by the ever-so-lovely Nuria Sanchez Garcia.

Nuria is now priming a bunch of schoolgirls to play the backhand. All executed with top-quality Babolats sent by Nadals official sponsors every year. Pichekinda Ramana? she yells in Telugu,asking if Ramana,13,is mad. She hasnt crossed the net once,not once in an entire session. Si,lo siento teacher,lo siento, says Ramana in Spanish,furiously apologising for her lack of ability. Its fine,says Nuria with a smile and a nod. Tomorrow morning,at 6,Nuria and Ramana will try again.

The buses,patiently parked outside,wait to take the kids back. Back home from the middle of nowhere.