The born again terrorist

Less than a fortnight after Heathrow, another scare aboard a Northwest Airline flight has the world’s headlines. Perhaps we’d be less scared if we learnt more. There is no convenient ‘us’ and ‘them’ when it comes to terrorism. ‘Converts’ who join the jihad are a case in point

Yesterday, a Mumbai-bound Northwest Airline flight from Amsterdam turned back after the crew grew suspicious of some passengers. Later, an official of the US government is reported to have “unofficially” said that the passengers were passing cell phones among themselves while the airliner was taking off: “It was behaviour that the average passenger wouldn’t do…” Spotting a terrorist isn’t easy. But if we were to try spot one, it would serve us better to know that the key to his identity doesn’t lie in stereotypes.

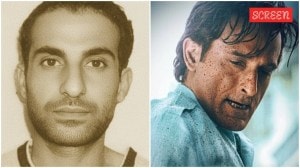

Take the case of the last big terror story that played itself out at Heathrow on August 10. Three out of the 23 people arrested in connection to the plot to blow American airliners over the Atlantic are not born muslims but converts. A story on one of the suspects arrested, Don Stewart-Whyte, in the British daily The Sun was headlined “Born a Christian”. The 19-year-old son of a late Tory politician is said to have converted to Islam last year. For many Britons, this is one of the most unsettling aspects of the case. But for many specialists of terrorism in Europe, this comes as no surprise.

Each year thousands of men and women convert to Islam in Europe and the US. Only a tiny minority is drawn to its most extremist forms, but this percentage has been growing significantly in the last years. Richard Reid, the so-called “shoe-bomber” who tried to blow up an American Airlines flight in 2001 is a British convert. John Walked Lindh, the 20-year old Californian who fought with the Taliban in Afghanistan converted when he was 16. In November 2005, Muriel Degauque, a Belgian woman became the first convert suicide bomber in Iraq. France’s Renseignements Generaux (police’s intelligence service) estimates that 3.2 per cent of the 50,000 French converts to Islam are connected to some form of radical Islam, a higher percentage than among non-convert Muslims. This has compelled authorities and observers alike to find explanations to the phenomenon, whether socio-economic, political or psychological.

Is there a typical profile to converts drifting to the “terrorist career path”? No serious pathology pattern emerges from studies. But the individuals drawn to this path seem to generally come from underprivileged neighbourhoods in urban environments, with little or no job prospects and very often living in a small underground economy of delinquency. Richard Reid who converted while in prison, experienced a life of crime and a broken family. According to a Renseignements Generaux study released in 2005, converts in France are 83 per cent male and have a median age of 32 years. Half of them are unemployed and more than half have no diploma. Many come from troubled family backgrounds. And 44 per cent chose a Salafist-inspired form of Islam (most rigourist). Often alienated and socially marginal individuals, they face a lack of identity and meaning. Still, what can explain this further and dramatic step – the “conversion” for some of them to terrorism?

Converts have been a prime recruitment target for terrorist groups for their ability to operate and travel freely in Europe, Asia and North America with less risk to arouse the suspicion of security authorities. Beyond their usefulness, a number of significant factors should be mentioned. First, there is the notorious “convert’s zeal”. There are countless examples through history of newly converts (whether to a religion or a doctrine of any kind) displaying an extreme version of the newfound “truth”. The new member of the community feels the need to prove his faith and commitment and therefore adopts behaviors at times more rigorist than a ‘native’ of the same community. Also, conversion often happens within one group, with one version of the religion being taught. The convert is thus more likely to develop a dogmatic vision and understanding, whereas someone who grew up in a certain belief system is more likely to be exposed to a variety of interpretations over time.

Several mechanisms of rejection of the convert’s background occur. When conversion is an answer to feeling alienated and disconnected from one’s society, the individual is tempted to reject his (or her) former world, and demonstrate how bad it is. This, by contrast, will constantly help justify and reinforce his new choice. Olivier Roy, one of France’s experts on radical forms of Islam, explains that converts choosing terrorism are mostly white youth from depressed suburbs, who by becoming a shahid (martyr), help destroy the impure societies they are coming from — and which originally rejected them. Jamaican-born Germaine Lindsay, one of the four suicide bombers in London’s July 2005 bombings, converted at the age of 15, putting an end to his drug dealing activities, and leaving behind all his previous friendships. During his trial, Richard Reid explained that although he knew he would cause untold pain and grief, his act was justified by the desire to “die for his family” and avenge what he believed was the killing of millions of muslims by Western countries.

Psychological and sociological studies reveal that in large-scale industrial societies, socially marginal individuals, especially adolescents, with high stress levels and low self-esteem, are more likely to pursue a religious identity, often of the most dogmatic kind. The new-found identity frequently results in a diminished personal autonomy and increased dependency on a community and strong leadership. Terrorist groups share a lot with some authoritarian sects, with a requirement for total commitment, a set of regulated beliefs and behaviours, a tendency to authoritarian aggression (rejecting “deviant” attitudes and outsiders). The various psychological and socio-economic issues faced by the individual find a different “conduit” to be channeled through, as time and external circumstances vary — yesterday it could be a far-left group such as the Red Army Fraction in Germany, or elsewhere the Japanese Aum Shinrikyo cult, today it finds at times an expression through some radical groups of Islam, tomorrow it may take some other form. Of course belief and ideology aren’t to be discounted, but in understanding the convert’s “conversion to terrorism”, the challenge is for society, and for the individual concerned, is to face the internal forces and core issues that push him or her towards such an extreme “conduit”.

The writer is a French journalist with a special interest in applying psychological tools to international relations.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05