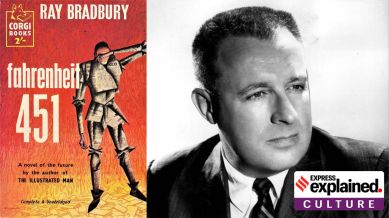

Remembering Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451: why his pioneering critique of censorship remains relevant today

In the birth anniversary week of Ray Bradbury, a look at what his Farenheit 451 was all about, and why it remains relevant, 71 years after its publication.

This was the birth anniversary week of the American writer Ray Bradbury, the author of Fahrenheit 451 which, 71 years after it was published, remains one of the most iconic critiques of censorship and mass conformity ever written.

Fahrenheit 451 itself faced censorship, editing, and criticism for a variety of reasons from “dirty, vulgar talk” about drugs and portraying a Bible being burned to supposedly defaming firefighters.

Here’s what the book was about, and why it is more relevant than ever today.

The novel, Fahrenheit 451

The novel, published in 1953 at the height of the “McCarthy era” of political repression and persecution of left-wing individuals and ideas in the United States, describes a dystopian society where books are banned, and “firemen” like the protagonist Guy Montag, are hired to burn them.

When Montag’s wife, Mildred, attempts suicide and fails, she forgets the whole act by the next morning — because she is transfixed by the four television-covered walls of her room.

This event, and others such as meeting someone who asks him if he’s happy, watching a woman choose to die with her books, and hearing frivolous chatter about war, catalyse Montag to rethink his job. He plans to read books he had stashed in a closet, but he must brave many obstacles in his daily life to begin doing so.

Bradbury, who was widely considered as an author of science fiction, himself saw only Fahrenheit 451 as fitting the genre. “I use a scientific idea as a platform to leap into the air and never come back,” he once said.

The burning of books

“A book is a loaded gun in the house next door. Burn it. Take the shot from the weapon,” says Captain Beatty, Montag’s boss in the book. “We’re the Happiness Boys,” Beatty tells Montag. “Don’t let the torrent of melancholy and drear philosophy drown our world,” he says. Books cause constant unrest, he says, because they incite people to “think for themselves”.

The burning of books, often as a public spectacle, has long been used by authoritarian regimes to send out similar signals. The best known example is that of Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich when, beginning May 1933, Nazi student groups lit massive bonfires of books that they declared “un-German”. Among the books they targeted were those by the socialist philosophers Bertolt Brecht, August Bebel, and Karl Marx, and the authors Thomas Mann and Ernest Hemingway.

But the dark history of ritual book burning, also known as biblioclasm or libricide, goes as far back as the destruction of Maya and Aztec codices in the 15th and 16th centuries, the razing of the House of Wisdom library in Baghdad by the Mongol armies of Hulegu Khan in the mid 13th century, and even the burning of Confucian texts by the order of Emperor Shin Huang of the Qin dynasty in late third century BCE China.

Book bans in today’s world

Book burnings these days are mainly isolated acts by individuals or vigilante groups who often claim to act in retaliation for a perceived offence caused to their religious or cultural beliefs, or as an expression of contempt for the contents of the book or its author. However, many books, films, and works of art face a range of official and unofficial restrictions of varying severity in countries around the world.

Prominent victims of such direct or indirect censorship for a wide range of reasons — including allegations of profanity, hurting religious sentiments, and defamation — in India and abroad include the authors D H Lawrence (Lady Chatterley’s Lover), Salman Rushdie (The Satanic Verses), and Taslima Nasrin (Dwikhondito, Amar Meyebela, Lajja, etc.).

According to a 2024 report by PEN America, a rights group that documents such restrictions yearly, “There were over 4,000 instances of book bans in the first half of this school year — more than all of the last school year as a whole” in the US. The authors everywhere have always defended their right to individual expression and freedom to critique, especially in opposition to majoritarian ideas.

Continuing relevance of Fahrenheit 451

The ideas of freedom of thought and expression that lie at the heart of Bradbury’s book are under threat around the world. A corollary of the regimentation of thought and the closure of minds has been the rapid spread of misinformation on the Internet, which poses serious threats to peace, harmony, and the rule of law. Intolerance of a range of opinions has increased the levels of polarisation in society, and a shrinking of the middle ground that is critical especially in democracies.

In an interview given during his lifetime, Bradbury pointed out that “If people can’t read, if your educational system fails and people can’t read or write, then they’re at the beck and call of everyone with a flimsy idea.”

Critically, throughout Fahrenheit 451, Bradbury never identified any minority by name. While the bulk of the book focused on critiquing the government’s powers, Bradbury presciently acknowledged that it could equally apply to the “political correctness” that he said had emerged within certain social groups.